To many communication experts I have the opportunity to speak with, I ask the same question: which speech do you think is better: Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech or Steve Jobs’ speech at Stanford University? Some lean towards King, others towards Jobs. There’s no definitive answer to this question. Both speeches are considered outstanding, making it difficult to determine which is superior. So, today let’s take a closer look at one I haven’t yet analyzed here—Steve Jobs’ speech at Stanford, delivered on June 12, 2005.

The Origins of the Stanford Speech

In February 2005, Jobs contacted a renowned speechwriter, Aaron Sorkin. He sent him his notes, but the speechwriter remained silent for a long time. In April, Jobs followed up with a reminder—they spoke on the phone, to which Sorkin reportedly responded dismissively, “Oh yeah.” After sending him another set of notes, Jobs managed to speak with the speechwriter again. The response? Simply “Uh-huh, uh-huh, okay,” and nothing more. Sorkin stopped answering Jobs’ calls entirely after that.

By June—mind you, the speech was scheduled for June 12—a panicked Jobs was forced to write the speech himself. Allegedly, he wrote it in a single night, consulting his wife for feedback.

A small suggestion: if you’ve never watched this speech, it’s time to catch up. The entire speech is available on YouTube; simply search for “Steve Jobs Stanford.” There’s even a version with Polish subtitles. And for those who’ve already seen it once in their lives—watch it again. And then one more time.

Personally, I revisit this speech several times a year. I admit, it’s my favorite. I know no finer one. It contains not only the wisdom of a man who achieved great success and brushed with death but also rhetorical craftsmanship on a unique level. It is rich in content, condensed into just 15 minutes. There’s simplicity, but also narrative finesse. There’s depth of thought, but also straightforward, unpretentious sentence construction. It contains humor, emotion, and deeply personal, intimate confessions. The entire speech is an emotional rollercoaster.

This rollercoaster took Stanford graduates on a memorable ride. The convention of the address is unique. American colleges have a tradition where, at the end of the academic year, a distinguished personality delivers a message to the graduates. These speeches are called “commencement addresses.” Some become classics. Some even change the course of history—like General Marshall’s 1947 speech at Harvard University, which announced the financial aid plan for war-ravaged Europe, later known as the Marshall Plan.

Jobs’ speech at Stanford didn’t change the course of history, but it is undeniably recognized as the greatest commencement speech in history.

The Setting and the Surprising Decision

That Jobs decided to deliver this speech surprised many close to him. Until then, he had avoided lectures and talks unrelated to Apple product launches. But it was 2005. Jobs had just turned 50, and a year and a half earlier, doctors had diagnosed him with pancreatic cancer. According to his biographer, Walter Isaacson, he was in a reflective mood. He wanted to share his vision of how the young Stanford graduates could try to shape the world.

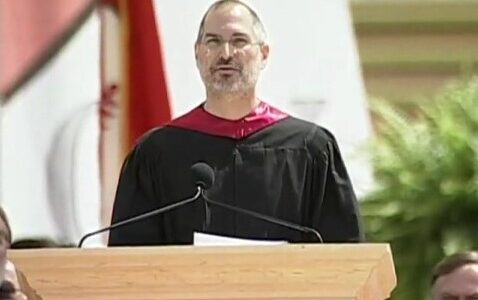

In one YouTube recording, you can see not only Jobs’ speech but also the somewhat lengthy introduction by Stanford’s president, John Hennessy. The introduction, let’s admit, is dull, but the frame is interesting. In the background, you can see Steve Jobs himself. Sitting behind the president, waiting his turn, he is completely calm and focused. He takes a sip of water, changes his glasses to reading ones, and glances at his notes. There’s no visible nervousness, no fidgeting. He stands up, walks to the lectern, and starts speaking like a professional. Well, that’s exactly what he was—a professional speaker with many public appearances to his credit, endowed with great charisma and an awareness of that charisma.

A Masterful Start

The opening of the speech is already masterful. Like a professional, in line with the accepted convention, he begins with a few warm words about Stanford University:

“I am honored to be with you today at your commencement from one of the finest universities in the world.”

This isn’t about flattery. It’s about building a connection. This is a classic rhetorical principle—show the audience you value them, and they’ll give you their attention. It’s a kind of contract.

Then he immediately breaks away from the formal tone with humor and self-deprecation:

“I never graduated from college. Truth be told, this is the closest I’ve ever gotten to a college graduation.”

Intriguingly, Jobs continues, saying: “Today, I want to tell you three stories. That’s it. No big deal.” Jobs immediately signals that these will be stories—not a lecture. Graduates, after years of studying, are likely tired of lectures. But stories—that’s different. Everyone likes to listen to stories. Thus, from the outset, he wins the audience’s favor—they know they’re in for something unconventional.

A Speech Worth Watching Again and Again

I won’t summarize the speech—it’s worth watching and listening to in its entirety. Instead, I’ll highlight a few things that, from my professional perspective as someone working in communication, are worth noting, appreciating, and emulating.

Humor in the Speech:

- When Jobs says this is the closest he’s ever gotten to graduating from college.

- When he mentions attending Reed College, which was “almost as expensive as Stanford.”

- When he humorously claims dropping out of college was the best decision he ever made, to the audience’s great amusement.

- The biggest laugh comes when he says: “If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts. And since Windows just copied the Mac, it’s likely that no personal computer would have them.”

Personal Confessions with Details:

Jobs doesn’t shy away from deeply personal admissions, describing events in vivid detail. For instance:

“Last year, I was diagnosed with cancer.” He continues with specifics: “I had a scan at 7:30 in the morning, and it showed a tumor on my pancreas.”

Later:

“That evening, I had a biopsy, where they stuck an endoscope down my throat, through my stomach and into my intestines, put a needle into my pancreas, and got a few cells from the tumor.”

Though some might find the medical details excessive, they serve a purpose: every story needs details. Details not only make the story credible but also help the audience visualize it.

Memorable Statements:

Jobs makes powerful and brilliant assertions, many of which have become iconic quotes:

- “Even people who want to go to heaven don’t want to die to get there.”

- “Death is very likely the single best invention of Life.”

- “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.”

The Magic of Contrasts

Steve Jobs’s entire speech is constructed around the rule of three. The rule of three is an old rhetorical principle suggesting that arguments be grouped into threes. Jobs follows this principle by telling three stories—not two, not five, but three. Though one might argue the conclusion serves as a separate, fourth story:

- Connecting the dots

- Love and loss

- Death

Additionally, Jobs frequently uses triple arguments. For example, in this sentence:

“I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great.”

Or in the closing line, “Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish,” my favorite part. In this final segment, he delivers a call to action, repeating the phrase “Stay hungry, stay foolish” exactly three times.

Antithesis is another defining characteristic of Jobs’s speech. Antithesis involves juxtaposing two opposing concepts, thoughts, or ideas. He employs it in many parts of his speech, such as:

Dropping out – dropping in:

“The minute I dropped out I could stop taking the required classes that didn’t interest me, and begin dropping in on the ones that looked interesting.”

By using “dropping in” and “dropping out,” he creates a striking antithesis.You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.

The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again.

Love and loss—Here, not only is there antithesis, but also alliteration, as both words start with the same sound.

The core antithesis, however, lies in the very essence of the speech. In my opinion, what made this speech so popular was that Jobs combined two opposing styles: light and heavy.

The Light Style: Humor, simplicity, and the impression that he’s not giving a formal lecture but just sharing some thoughts with young people. The introduction—“three stories, not a big deal”—is light in tone.

The Heavy Style: Heavy in terms of the gravity of the topics. Jobs doesn’t talk about light or trivial matters. He discusses death, loss, adoption, rejection, dropping out of college, making tough life decisions, and ends by urging the audience to stay “hungry” (unsatisfied) and “foolish” (unreasonable). And this message—directed at graduates of one of the best universities in the world—is profound.

This isn’t a fluffy motivational talk or an MTV reality show. These are weighty topics. Yet, the combination of a light delivery with heavy subject matter creates something magical. This antithesis between lightness and heaviness is like the yin and yang of great speeches. And as I often emphasize in presentation and communication training, the secret to outstanding speeches lies in balancing opposing forces: generality versus specificity, the sacred versus the profane, or lightness versus gravity.

Take this passage:

“When I was 17, I read a quote that went something like: ‘If you live each day as if it was your last, someday you’ll most certainly be right.’ It made an impression on me, and since then, for the past 33 years, I have looked in the mirror every morning and asked myself: ‘If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?’ And whenever the answer has been ‘No’ for too many days in a row, I know I need to change something.”

This passage is emblematic of Jobs’s duality. The first sentence is humorous. Then, he transitions into serious reflection. Jobs reveals a personal morning ritual, and this juxtaposition—humor followed by gravity—is the essence of the entire speech. This way, the seriousness doesn’t become pompous, and the humor isn’t just for applause. The blend of styles from opposite poles gives the speech its depth.

Behind it all is the depth of Jobs’s thinking—reflections on 50 years of life filled with both successes and failures. Many 50-year-olds who’ve achieved success likely have similar thoughts. But what made Jobs exceptional was something few possess: remarkable communication skills that allowed him to articulate those reflections in a compelling way.

Yes, Jobs had immense talent as a communicator. I enjoy watching his old presentations or interviews from the early stages of his career. What strikes me in those interviews is that, as a 20-something, he already spoke with remarkable maturity. He always—always!—expressed himself in a structured manner. He wasn’t afraid of pauses, frequently used metaphors and analogies (very apt ones, too), and had a wide, diverse communication repertoire. He instinctively knew which tool to use at any given moment during public appearances. Of course, in his relationships with colleagues and loved ones, he often showed a different side—but that’s a story for another time.

Here are some of my favorite quotes from the speech:

- “I’m pretty sure none of this would have happened if I hadn’t been fired from Apple. It was awful medicine, but the patient needed it.”

- “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle.”

- “No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don’t want to die to get there.”

Excellent, not perfect

Is Steve Jobs’s Stanford speech perfect? Absolutely not.

The students I discuss this lecture with point out a few weaknesses: that Jobs read from a script instead of speaking off the cuff, that he seemed to be lecturing young people. Well, those arguments don’t resonate with me.

He read from a script—because that’s the convention for this type of commencement speech. Was he lecturing? Not in my opinion. He said very interesting things.

I might suggest one adjustment that could have been made: despite the many pauses he used between points, he could have included even more pauses and made them slightly longer—especially when saying something that elicited applause from the audience. Instead of waiting for the cheers, laughter, and clapping to subside, he rushed forward with his speech. From a public speaking technique perspective, that’s a mistake—many people might have missed his words amidst the noise of the applause and laughter.

Another point: he could have established better contact with the audience—smiling, looking at the crowd for a bit longer. He could have scanned a larger portion of the script, memorized it, and delivered it while looking ahead.

Nevertheless, these are minor points that don’t detract from the overall quality—and the overall quality is outstanding.

One thing, however, does intrigue me. A few years ago on YouTube, anyone could see detailed statistics for a video’s views. Not just the number of views and likes (thumbs up) but also the number of dislikes (thumbs down). Today, you can no longer see the statistics for dislikes—but it was striking that around 10% of the ratings for this speech were negative. Yes, 10% of people disliked this speech. Really? Well, to me, this is just confirmation that the world has no shortage of grumblers.

So, if you’re giving any kind of presentation—don’t worry if not everyone likes it. Even the most brilliant speech by a master like Steve Jobs doesn’t please everyone.